Hey y’all,

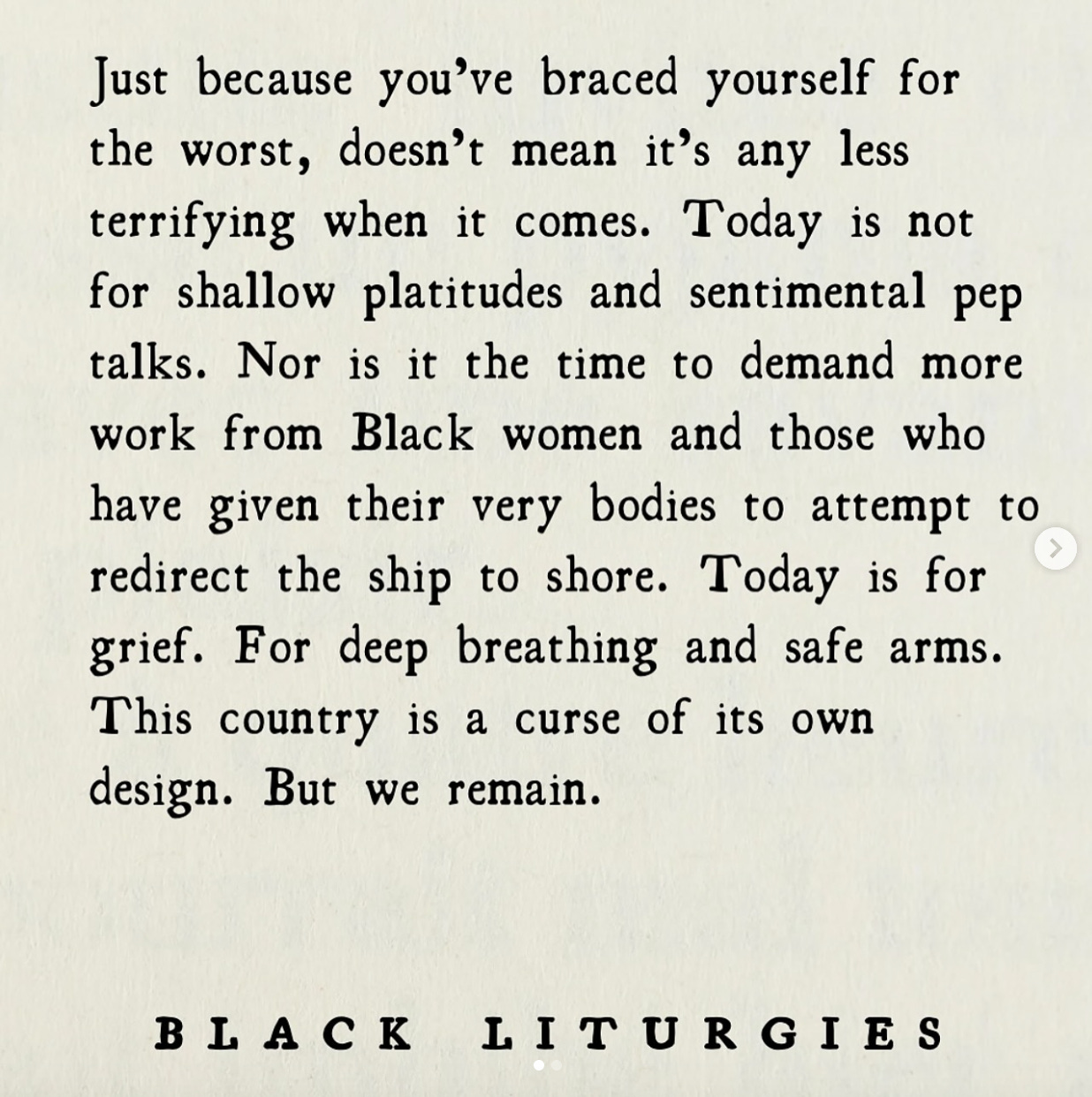

I saw this post on Instagram last Tuesday via @blackliturgies:

I shared it on my stories, in the family group chat, and now I’m sharing it again here. It is a reminder that we don’t always have to be the bigger person. We don’t always have to “find the good”—we can be upset, we can be scared, and we can grieve. Deep down, we know we won’t always feel this way, but it’s okay to feel what you feel as it comes with no regard for the future you’s emotions.

It doesn’t take away from the light that will always remain embedded within our souls or the joy that we are so famously known for. It’s just the reality of the situation, and sometimes that’s where we need to reside—in the reality. The reality is, America voted for hate, bigotry, and racism. They voted for xenophobia, misogyny, and illiteracy. Whether you’re choosing to divest, rest, or fight even harder, make room for how you feel and let that emotion flow like a river.

This Week’s Story

The plus-size and body positive movement of the early 2010s took off and we never looked back. Of course, plus-size women should be able to find stylish clothing that fits. Of course, plus-size women should have an array of choices just like everybody else. But what about women who are considered “too small?” Why didn’t the size inclusivity pendulum ever swing the other way? In this week’s essay, writer Rejoice Anodo explores how she felt left out of the body inclusivity movement because of her “too small” size.

Take care,

Anayo Awuzie

EIC of Carefree Media

Black Women Can Be Small Too

by Rejoice Anodo

TW: body image

Recently, I moved home from university on vacation to escape the bustle of student life. During this time, I reconnected with childhood friends and rummaged through old keepsakes—handwritten notes from secondary school and wishlists I wrote before I went to college. I noticed that I'd achieved most of my goals except one: gain weight.

As a teenager, I used to think something was wrong with my body. I was small, not moderately thin in a way I could be considered lithe and modelesque, and not tall enough to be recommended for a prospective basketball career. Going shopping for festive occasions like weddings, Easter, or Christmas always left me feeling a different kind of way, like I had to make up for something I did not lose in the first place.

Year after year, the process was the same, and each trip to the market left a bitter aftertaste at the back of my throat.

During these market sessions, when I trailed behind the adult I was assigned to, I gawked at the mannequins placed strategically under multi-colored lights in shops. I wanted so badly to be shaped like those mannequins, so every dress I bought would fit just like it was on them. Interestingly, whenever the adult decided we'd found a suitable clothes store to buy a dress, the shop owner would provide the smallest size of the dress for me to test.

The changing room, with its chipped mirrors propped against walls, was my least favourite place to be, as it displayed the stark reality that, despite my fantasies, the mannequin and I had nothing in common.

Clothes that clung to the curves on the mannequins on display hung loosely on me. These dresses, usually round-necked, would hang low, exposing my clavicles; the armholes would have a few centimetres of free space around them, and the skirt area simply hung down unflatteringly from my waist. In moments of brief delusion, I’d gather a fistful of the dress at the back with one hand so that the dress looked like it fit. This reverie was always cut short by the trader, who prompted me to come out and show everyone my “fine dress." I’d walk out gingerly from the changing room, and the shop attendant would begin sharing adjustment tips to the adult on how to make the dress fit, in a mix of English and pidgin, gesturing often to underline their point.

“Let me give you my tailor’s number. If e hol’ am for waist, hol’ am for hand, the cloth don fit am be that”. The shop attendant said in broken English.

The adult would turn me this way and that, observing to see if theircalculations were feasible. Just like that, the market session would progress from the trader’s shop to the tailor’s shop for amendments, then to the cobbler's—to make extra holes for my belt so the dress would fit even more (yet another adjustment tip from the trader).

The shopping experience seemed to benefit everyone on a surface level—the shop gained their profit, the adult had accomplished yet another task, and I had gained a new dress. These dresses, with their floral patterns, beaded or embroidered necklines, and peplum, straight or wrap skirt regions, were supposed to help me embody femininity.

However, I felt less of myself in those dresses, proceeding to stick to walls in public spaces and among large crowds, and declining opportunities to take pictures while wearing them. They were pretty, and they looked good on other girls my age. It became obvious with time that my body was the limiting factor, and constant adjustments to dresses purchased at the smallest sizes was an unsustainable practice.

Going to university changed everything for me. I started buying my own clothes without needing an adult's guidance. I was initially overwhelmed by the multitude of choices available. Most retail stores had the same set of clothes strung on mannequins. They were mass produced, made of low-quality materials, and sold at ridiculously expensive prices. As much as they looked good, I could not stand the thought of wearing a dress I would most likely find on a stranger within a ten-meter radius. Thus, I ticked retail stores off my list.

Clothing stores in large markets were my next option. I still harboured some distrust for the traders due to my experiences as a young girl, so I decided to take their advice with a pinch of salt. These ready-made dresses came in different sizes, but most of the time, even the smallest sizes could not fit. Still, I bought them a few times and adjusted them accordingly to wear to corporate occasions. I admit my first purchases were a bit overpriced, partially because I instantly lusted over the dresses I liked, and I was often perceived as a teenager who was sent to the market alone.

I eventually discovered the gem of thrift stores, which sold second-hand clothing, shoes, and bags. I was able to pick out clothing pieces to match what I already have to make unique fashion statements. I began to worry less about wearing the exact same outfits as others.

I also began to pick out styles that flattered my body type as a size zero. Instagram provided most of my inspiration. By looking at Black influencers with similar body types as mine, I grew to be confident in my wardrobe choices. These helped me make customized dresses that didn’t need to be adjusted before I wore them.

I also began to expand my choice of clothing beyond just dresses. With a focus on being modest, I paired skirts with shirts, tank tops, and combat pants, to the extent at which I felt comfortable. While I haven’t gained weight in the way I desire, I am slowly unlearning the harmful notions I bore concerning my body as a teenager. Although I have made considerable progress, I still shy away from pictures, even in dresses I consider to be pretty and well-fitted.

The numerical system used in clothing charts often places Black women between sizes 14 and 18, with the figures descending as low as 6 or extending up to 20 and more. While I applaud the efforts made at promoting inclusivity in fashion, there seems to be a grey space where Black petite women, between the sizes of 0 and 4, have limited options for clothing choices.

Body positivity in fashion should extend to both ends of the spectrum. More fashion houses should include ready-made outfits for casual and special occasions that fit all body types. Brands with predominantly Black and African consumers can do better by expanding their clothing choices beyond what an average Black woman looks like; Black women can be small too.

Rejoice Anodo is a creative writer and freelance journalist. Her work explores history, culture, feminism, and women's rights.

I love this! I've also been thin my whole life and as a black woman, it felt almost wrong.

I love this. I was always thin growing up and it made me feel very insecure. In High school I try so many things to gain weight. It’s very sad that as a black girl/woman society makes it that we should all be thick and a certain size. It took me years to love my size and not give a damn.